ReviewMeta Analysis Test: Reviewer Participation

At ReviewMeta, we look for patterns beyond the reviews themselves by looking at the data that we gather from the reviewers themselves. Our Reviewer Participation test examines the history of all the reviewers of a given product and can help identify unnatural patterns. A reviewer’s participation is the number of reviews they have written. While we can’t conjure a whole lot from an individual participation number, we can start to identify patterns when looking at the participation of all reviewers of a specific product.

Here is how it works:

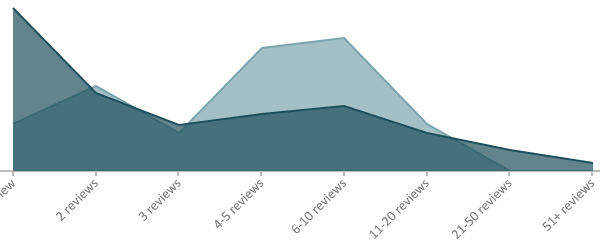

First, we place every review of a given product into an participation group. For example, a review written by someone with 2 reviews will fall into the “2 Review” group, a review written by someone with 14 reviews would fall into the “11-20 Reviews” group, and a review by someone with 4,000 reviews (yes, these reviewers do exist) would fall into the “51+ Reviews” group. This allows us to see the distribution of participation groups for the product.

Just a product’s participation group distribution doesn’t tell us a whole lot on it’s own. Without being able to compare the product’s distribution to an expected distribution, we can’t say what groups are suspicious; there is no participation group that is always suspicious or unnatural. To find our expected participation distribution, we pull data about the participation groups for every review in the category. We then compare the participation distribution of the product with our expected distribution and identify any groups that have a higher concentration than what we’d expect to see.

There are several reasons we’d see a participation distribution that is different than what we’d expect, but all of them indicate that there may be unnatural factors at play.

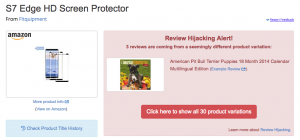

- A brand might have offered an incentive for customers or fans to review their product. This might result in an increase in people who don’t normally write reviews to write a review, causing a spike in the lower participation levels.

- A brand might be using a third party service to help find reviewers they can send their product out to for free in exchange for a review. This would result in a disproportional amount of reviewers having a high level of participation.

- A brand might be creating sockpuppet accounts that all review the same products, creating a spike in that participation group.

- A brand might be using a third party service to completely manufacture reviews, creating a spike in a specific participation group, depending on the strategy that the third party service uses to create those reviews. Often times you’ll see a spike in accounts in the 51+ review level, but other times they will be more cautious and only review up to a certain amount of products per account to try and fly under the radar.

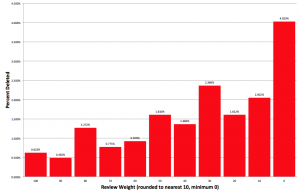

If we find any overrepresented participation groups, we’ll list each one in the report, and add them up to see what percent of the product’s reviews are in these participation groups. While it isn’t uncommon to see a small percentage of reviews in overrepresented participation groups, an excessively high number can trigger a warning or failure of this test. Furthermore, if the average rating from the reviews in overrepresented participation groups is higher than the average rating from all other reviews, we will check to see if this discrepancy is statistically significant. This means that we run the data through an equation that takes into account the total number of reviews along with the variance of the individual ratings and tells us if the discrepancy is more than just the result of random chance. (You can read more about our statistical significance tests here). If reviews in overrepresented participation groups have a statistically significantly higher average rating than all other reviews, it’s a strong indicator that these reviewers aren’t evaluating the product from a neutral mindset, and are unfairly inflating the overall product rating.

Keep in mind that the individual reviewer participation isn’t what we’re looking at here. A reviewer with 40 reviews isn’t necessarily any more trustworthy than a reviewer with 4 reviews. However, if every reviewer of a product has 40 reviews, it’s much more suspicious than a product with an even distribution of reviewer participation.

you created a line graph for “Reviewer Participation”…however it appears that the data is in buckets not a data point per # of reviews; nor is this a time series. Shouldn’t this be a column/bar graph and not a line graph? (if you say its an area graph, my comments still stand).

It’s more of an area chart, but I think the most important thing here is to show the comparison to what you’d expect in the category, which I feel is best visualized by the selected chart type.

This is absurd. So my reviews are less trustworthy as I’ve made too may reviews? It’s those who give 5 stars all the time and write lots of reviews that should have a smaller trust rating, not myself whose average rating is 2.9!

Hi Ian-

Please re-read the article – it’s never as simple as having “too many reviews”. The weight assigned by the Reviewer Participation test is determined from review to review, not assigned to a reviewer. So if you have 40 reviews, and you review a product where ALL the reviewers have 40 reviews, we may devalue that review. However this would NOT affect your other reviews.

So what about my review of the myth of an afterlife? Are you saying other people have wrote a similar number of reviews to myself? If so, that is purely coincidental.

If my review were a fake one, do you really *really* imagine I would write 5,000 words??

I am very dyslexic so I might have misunderstood the article but I think It not about any one person. The word meta title of the article implies that the tests lumps something in groups and analyzes the groups.

It’s saying if all or even 80 percent of the reviewers of “ book title here” have written 10 reviews for other Amazon products, something unnatural might be happening.

For example, the company or author might be hiring people who have a similar experience level writing reviews.

It’s not saying that you were necessarily one of the hired people. Maybe you happen to just have the same amount of experience with Amazon reviews as the 500 other people the company hired.

Nonetheless, since something fishy might be happening one has to wonder about every review from the entire group of people who have say 8 to 10 other reviews on Amazon.

It’s questioning the group of reviewers as whole because 95% of them might have been hired.

Since the site can’t determine which, if any, were found through “Weasels for Hire Employment Agency, LLC “ via a job posting somewhere that said “ minimum experience of writing 10 or more reviews on Amazon required” in the experience required section of the job description, and which were the honest group who just happened to have 10 other reviews posted, it’s just questioning the entire group just to be on the safe side.

It’s like how the owner of a 24 hour store might question the integrity of everyone on the night shift if a diamond necklace went missing from his private office, after he went home following the afternoon shift. Let’s say the security cameras malfunctioned and everyone on the night shift knew where his extra office key was.

Since he can’t determine exactly who took it under those circumstances, everyone who was working during the window in which it was stolen is under suspicion. They might even all be fired. At any rate, they will probably all be questioned and it would be silly for any of them to take it personally.

Just a creative thought. Maybe a brief animated video with something funny like Weasels for hire LLC would help people better understand the red flags that come up in this situation. If I had the tiniest amount of animation experience, I would volunteer to make the video for you guys